Notes

September 2025

Note (2025-09-30 22:42)

“The History of the New Yorker’s Vaunted Fact-Checking Department”:

I’ve never encountered a complete description of what the magazine wants its checkers to check. A managing editor took a stab in 1936: “Points which in the judgment of the head checker need verification.” New checkers, upon receiving their first assignment, are instructed to print out the galleys of the piece and underline all the facts. Lines go under almost every word.

The joke in the department was that my foreign language was sports.

A disputatious source is actually more helpful than the opposite. The checking system, like the justice system, requires something to push against.

Checkers don’t read out quotes or seek approval. Sources can’t make changes. They can flag errors, provide context and evidence. The checker then discusses the points of contention with the writer and the editor. It’s an intentionally adversarial process, like a court proceeding. You want to see every side’s best case. The editor makes the final call. In a sense, the checker is re-reporting a piece, probing for weak spots, reaching a hand across the gulf of misunderstanding.

Peter Canby’s philosophy was that it’s better for a subject to scream before a piece is published than after—a controlled explosion. Screamers still provide useful information. They’re better than ignorers or trolls.

Most writers appreciate having been checked but resent being checked. Checking makes evident how badly you’ve misinterpreted the world. It upsets your confidence in your own eyes and ears. Checking is invasive.

“This kind of fact checking wasn’t nitpicking and wasn’t just a bureaucratic thing. It was an artistic advance of the twentieth century. It just clicked with modernism.” He went on, “Modernism is goodbye to self-expression, hello to what’s right in front of you,” and that means you better get the thing right. The hedge is an acceptance that the world is impossible to know accurately. It imparts to the writing a humbleness, an understatedness, and, perhaps, a smug fussiness: in other words, what people think of as The New Yorker’s voice.

Note (2025-09-25 22:23)

So, inconstancy, fallibility, forgetfulness, suffering, failure — these, apparently, are the unautomatable gifts of our species. Well, sure. To err is human. But does the AI skeptic have nothing else to fall back on than an enumeration of mankind’s shortcomings? Are our worst qualities the best we can do? It’s hard not to read the emphasis on failure as an ambivalent invitation for the machines to succeed.

The way out of AI hell is not to regroup around our treasured flaws and beautiful frailties, but to launch a frontal assault. AI, not the human mind, is the weak, narrow, crude machine.

For publishers, editors, critics, professors, teachers, anyone with any say over what people read, the first step will be to develop an ear.

Whatever nuance is needed for its interception, resisting AI’s further creep into intellectual labor will also require blunt-force militancy. The steps are simple. Don’t publish AI bullshit. Don’t even publish mealymouthed essays about the temptation to produce AI bullshit.

Note (2025-09-24 22:41)

“Inside Uniqlo’s Quest for Global Dominance”:

“Uniqlo is kind of like Everlane without the moral superiority and H&M without the ickiness.”

An inadvertent moment of unibare—a Japanese word for the moment when someone realizes you’re wearing Uniqlo and not a more expensive brand.

Uniqlo is the universal donor of fashion, intended to go with any life style or aesthetic.

What was clear is that Uniqlo conceives of itself as a distribution system for utopian values, replete with mantras and koans, as much as a clothing company.

[The LifeWear messaging for Uniqlo] was deliberately enigmatic, saying that he wanted customers to “stop a moment and engage with language.”

Yanai has likened Uniqlo to K-pop, an industry that is oriented toward “what will be popular worldwide, rather than focussing on uniquely Korean characteristics.”

Under normal circumstances, the Uniqlo shopper should walk into a store and feel a sense of overwhelming abundance. Such is the logic behind Uniqlo’s power walls of thousands of sweaters on shelves that reach so high you fear that they might bust right through the ceiling, like Willy Wonka’s elevator. The display is arranged according to a precise formula, with sizes increasing from floor to ceiling, and colors darkening from left to right, as well as from the entrance to the back of the store.

Each pile is assessed for tidiness multiple times a day, using a five-rank grading system. A “B” grade might mean that a green blouse has found its way into a blue stack, while “D” is reserved for serious cases like a completely empty stack, or items that have fallen on the ground. Like IKEA, which intentionally musses and jumbles its displays, Uniqlo believes that volume is the catalyst of consumer desire. Conway explained, “We want everything to appear fully stocked all the time.”

Apparently, one of Yanai’s inspirations for this hands-off style of service was a visit that he made to a university co-op during a trip to the U.S.; Uniqlo now trains employees to sell clothes like they are selling books, letting customers browse freely.

This strategy gives customers “a chance to say, ‘I don’t need a basket, but I need help with a sweater.’ It’s an indirect way to initiate communication—low pressure, because you’re offered something specific versus asking, ‘Can I help you?’ ”

Uniqlo finishes every zipper track with a small piece of fabric known as a “garage.” It keeps gunk out of the device and protects against abrasion. Other fixes are invisible.

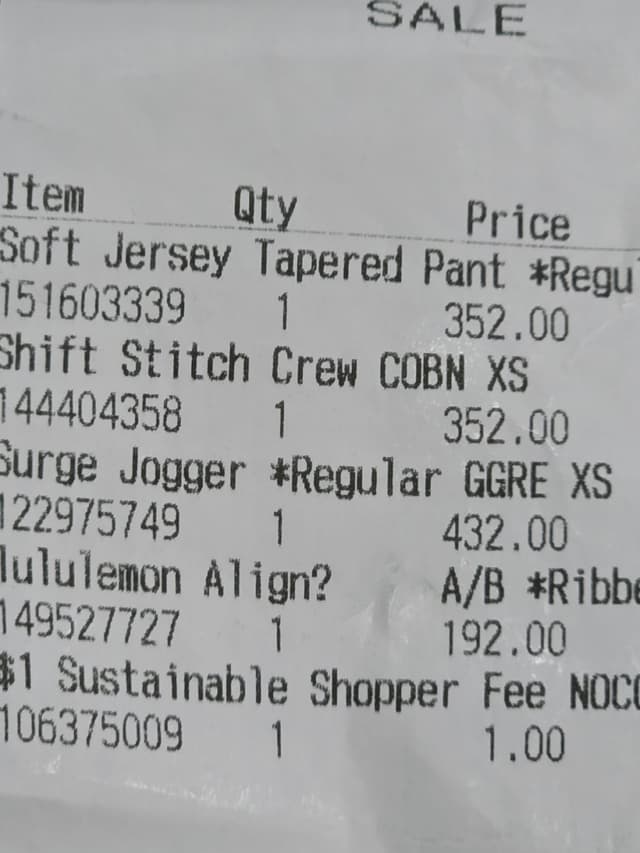

But much of what Fast Retailing says about its deep commitment to creating timeless clothes is undercut by the fact that it also owns GU, a lower-priced sister brand. Pronounced “jee-you,” GU offers “trend-driven styles” and “rapid turnaround times from design to retail”—with, presumably, rapid turnaround times from retail to landfill as well. And the scale of Uniqlo’s operations, not to mention its quest for endless expansion, makes real sustainability an impossibility.

Note (2025-09-24 22:27)

“Small Acts of Good, US as Third World Country, and How Culture Changes”:

For humans, it is another reminder we don’t help animals for them, but for us – to try and give our own pointless lives a little more meaning.

While we do help animals primarily to make us feel good, we do that because it is a reminder that there is a point to life, which isn’t grounded in the rational, but in the spiritual. Those daily acts of small “irrationality” are attempts to maintain our soul in an overly rational dehumanizing world.

These little acts of good, towards frogs, but especially towards other humans, is a part of us that speaks towards high purpose. Yes, I will use saving a tiny frog to imply the sacred dimension of existence.

Note (2025-09-24 20:00)

天下的性质不是世界主义(cosmopolitan)的政治正确秩序,而是为文明建立一种宇宙论式(cosmological)的生态系统秩序,考虑的重点是文明的生态安全,试图把世界变成每种生活方式和每种文化之间互相安全的系统,重点在“关系”的生态而不在“个人”的身份。最简略地说,天下体系是对亨廷顿的文明冲突问题的一个可能解。天下并不许诺类似神话的乌托邦(utopia),而是可实现的共托邦(contopia)。

从前人类有过多种“世界性”的努力,比如世界性的帝国、普世宗教、普世价值观、世界语之类,都失败了,其失败自有多种历史原因,但本质原因在于那些传统的世界性努力都属于单边主义的推广,只是单边之“化”而不是“互化”,即使一时成功也最终失败。孔子以为“名正言顺”就能够“事成”,现代政治学也以为“证成”的观念(justified,类似“名正言顺”的意思)就能够推广,这些传统理论都忽视了主体间性的根本难题是“他人不同意”,而“不同意”不需要也不服从名正言顺的理由。这是“他心”问题的极端形式。假如跨主体性能够成为一种解决方式,就需要发现能够形成“跨越”效果的方法,但似乎还没有发现充分有效的方法,因为“他心”有着难以进入的超越性。

Note (2025-09-21 23:29)

Note (2025-09-21 20:01)

Sappho. How to Be Queer: An Ancient Guide to Sexuality. Edited and translated by Sarah Nooter. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024.

In the words of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, queer “can refer to: the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically.”

Eros is above all a feeling so powerful that it is understood as divine, an affective force that draws people away from what is demanded of them by institutions and establishments, and toward an experience of fervent vitality.

A delicate fire

runs under my skin, my eyes

see nothing, my ears

roar,

cold sweat pours down me, and trembling

seizes me all over, and I am greener than grass.

A boy and a horse have a similar mind. For a horse

does not weep when his rider lies in the dust,

but just carries another man, once glutted on fodder.

For whoever labors for the love of a boy must, in essence,

put his hand over a quickly burning flame.

Blessed is he who, in love with a boy, does not know the sea,

and for whom night coming over the ocean is not a care.

For the vision of the mind begins to look sharp only when that of the eyes starts to abate from its peak.

Note (2025-09-20 22:37)

The virus of whataboutism produces at least two symptoms. On the one hand, it fosters apathy: if any form of criticism is just seen as hypocrisy, then what is the point of having endless discussions? When does one become qualified to criticise? On the other hand, it blinds by obscuring basic similarities, muddying the water and making it difficult to identify actual commonalities that extend beyond national borders and are inherent to the organisation of the global economy in our current stage of late capitalism.

The pervasiveness of the whataboutist virus also produces a powerful hyperactive immune response in the China debate that manifests itself as the very opposite of whataboutism—i.e. a complete dismissal of any attempt to find similarities between dynamics in China and elsewhere. This is a form of argumentation that can be defined as ‘essentialism’, in that it tends to emphasise the set of attributes specific to a certain context as its defining elements, a line of reasoning eerily reminiscent of the debates over China’s ‘national character’ (国民性) that raged in China and the West a century ago.

Essentialism also produces a myopic outlook, and often manifests as self-righteous outrage at any suggestion that there might be more to the picture than what immediately meets the eye. From this perspective, there can be no linkages, seepages, or parallels between liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes. China must be analysed in isolation, and any analysis must identify the authoritarianism of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the only constant underpinning all problems.

As easy as it is to lay the blame for all this on China—and undeniable as it is that the Chinese government is playing an important role in all this—these trends are not emanating solely from one country. Rather, what is happening in China is just one dramatic manifestation of global phenomena—phenomena that are, in turn, shaped by broader forces. For this reason, we need to go beyond essentialist and whataboutist approaches and carefully document (and denounce) what is happening in China, while also highlighting the ways in which Chinese developments link up with events elsewhere.

Note (2025-09-19 19:51)

Note (2025-09-19 07:21)

Note (2025-09-19 01:19)

like comfort foods there are comfort songs that you keep returning to when you just need something to fill in

Note (2025-09-18 19:43)

Note (2025-09-07 07:19)

reason to obey your mother’s order: was in the wild right before sunset when she texted today is 七月半 don’t go out after dark and be home before 9. i was like hahaha too late never mind. then i got semi-lost climbing up a stream and cut my thumb, which then failed the fingerprint match at the border check when i returned at 11

Note (2025-09-04 20:21)

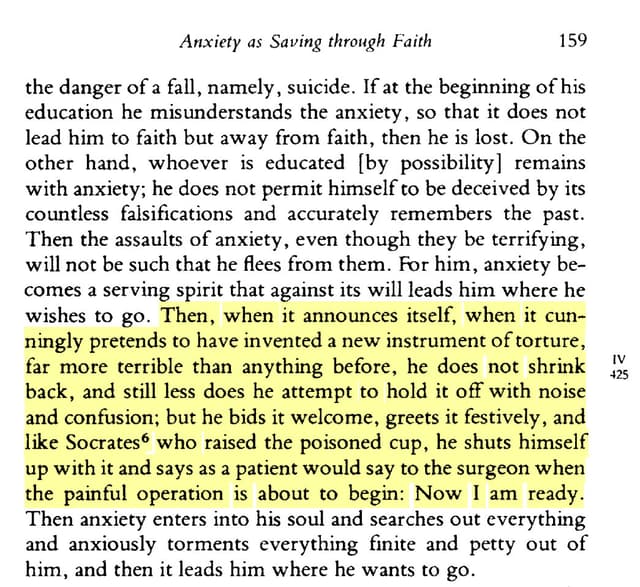

“look at the precipice with awe and rejoice in the proximity”

Note (2025-09-02 20:32)

August 2025

Note (2025-08-28 07:26)

Note (2025-08-27 12:19)

my recent litany against escalation: i might as well shut up

Note (2025-08-24 22:29)

Note (2025-08-23 09:39)

三点五十醒了,刷完了 feed,写了会东西,把 gpt 聊到了 quota,游了泳骑了车,吃了两顿,高兴了一会也自闭了一会,现在开始想今天怎么还没过完,或者今天已经过完了

Note (2025-08-22 17:13)

Note (2025-08-22 06:57)

Note (2025-08-22 01:34)

Note (2025-08-20 08:54)

也不知道老中为什么这么执着于把谢谢合作翻译成 thank you for your cooperation 在谢谢合作的语境里谢谢的如果不是合作难道还能是不合作吗