Notes

This section is intended for trivial amusements and ephemeral thoughts in their unorganized form — think of social media posts without interactions. Please allow for errors and imprudence. Also archived here is a selection of my older posts from Twitter and Weibo, neither of which I remain active on. Posts may be removed without notice if they are developed into formal articles or no longer reflect my current opinions.

Subscribe to these notes (excluded from the main feed).

January 2026

Note (2026-01-25 18:10)

Note (2026-01-22 23:31)

saw an article whose title i find particularly relatable — “i’m addicted to being useful.” so freaking i am.

Note (2026-01-19 20:55)

Note (2026-01-19 17:19)

Note (2026-01-18 12:41)

Note (2026-01-14 15:02)

Note (2026-01-13 22:17)

“How Consent Can—and Cannot—Help Us Have Better Sex”:

It’s widely accepted that a woman really can consent to sex with a husband on whom she is financially dependent. The immediate though rather less accepted corollary is that she can also consent to sex with a paying stranger. To say anything else, many feminists now argue, would be to infantilize her, to subordinate her—to the state, to moralism—rather than acknowledge her mastery of her own body.

Perhaps, some philosophers suggest, we should not be able to forfeit future consent, either by agreeing to serious bodily injury or death or by entering into a contract that strips us of long-term agency. But, if football players can consent to beat each other up on the field, why can’t we beat each other up in bed? If we want to forbid people from subjugating themselves in the pursuit of their fantasies, we’d have to criminalize both extreme forms of B.D.S.M. relationships and marriage vows that contain the word “serve.”

Critics of this shift worry about encounters where both parties are blackout drunk, or where one appears to retroactively withdraw consent. They argue that a lower bar for rape leads to the criminalization—or at least the litigation—of misunderstandings, and so discourages the sort of carefree sexual experimentation that some feminists very much hope to champion.

[T]he bureaucratization of our erotic lives is no path to liberation.

[A] cultural emphasis on consent—and especially “enthusiastic consent”—has divided “sex into the categories awesome and rape” (Fischel), ignored the complexity of female desire (Angel), and reinforced the notion of sex as something that women give to men, rather than something that equal people can enjoy together (Garcia).

Note (2026-01-13 22:00)

“Heidegger knew that we are always outside, weathering the storms”:

[W]e inhabit [the world] as that in and through which our lives take place and make sense. The world is not a container but the meaningful context in which we dwell. We are in the world in the way that someone is in love or in business.

It is in order to deny our facticity and its associated vulnerability that we want to think of ourselves as indoors. A sovereign, self-enclosed substance is not tied to the destiny of anything else. It does not depend on anything in order to be but exists all by itself. Thinking of ourselves in this way is a self-protective strategy. It purports to make us invulnerable: Deus Invictus, God invincible and unbound.

We are not and cannot be Deus Invictus but must be – if I may put it this way – Homo Implexus, the human being entwined and entangled. The truth is that we are vulnerable beings who live outdoors, amidst other things and at stake in them. To pretend otherwise is to deny the sober truth of your essential finitude as being-in-the-world.

So, if we try to pretend that we dwell indoors, we may win a faux feeling of invincibility. But we lose something more important: our openness to being moved. As Franz Kafka put it: ‘You can withhold yourself from the sufferings of the world; … but perhaps this very act of withholding is the only suffering you might be able to avoid.’

We can now see how being-in-the-world is like being in love. Not only is being in love a way of inhabiting a context of meaning, it is a way of allowing my life to become entangled in what is not up to me.

Note (2026-01-04 21:03)

Note (2026-01-01 22:02)

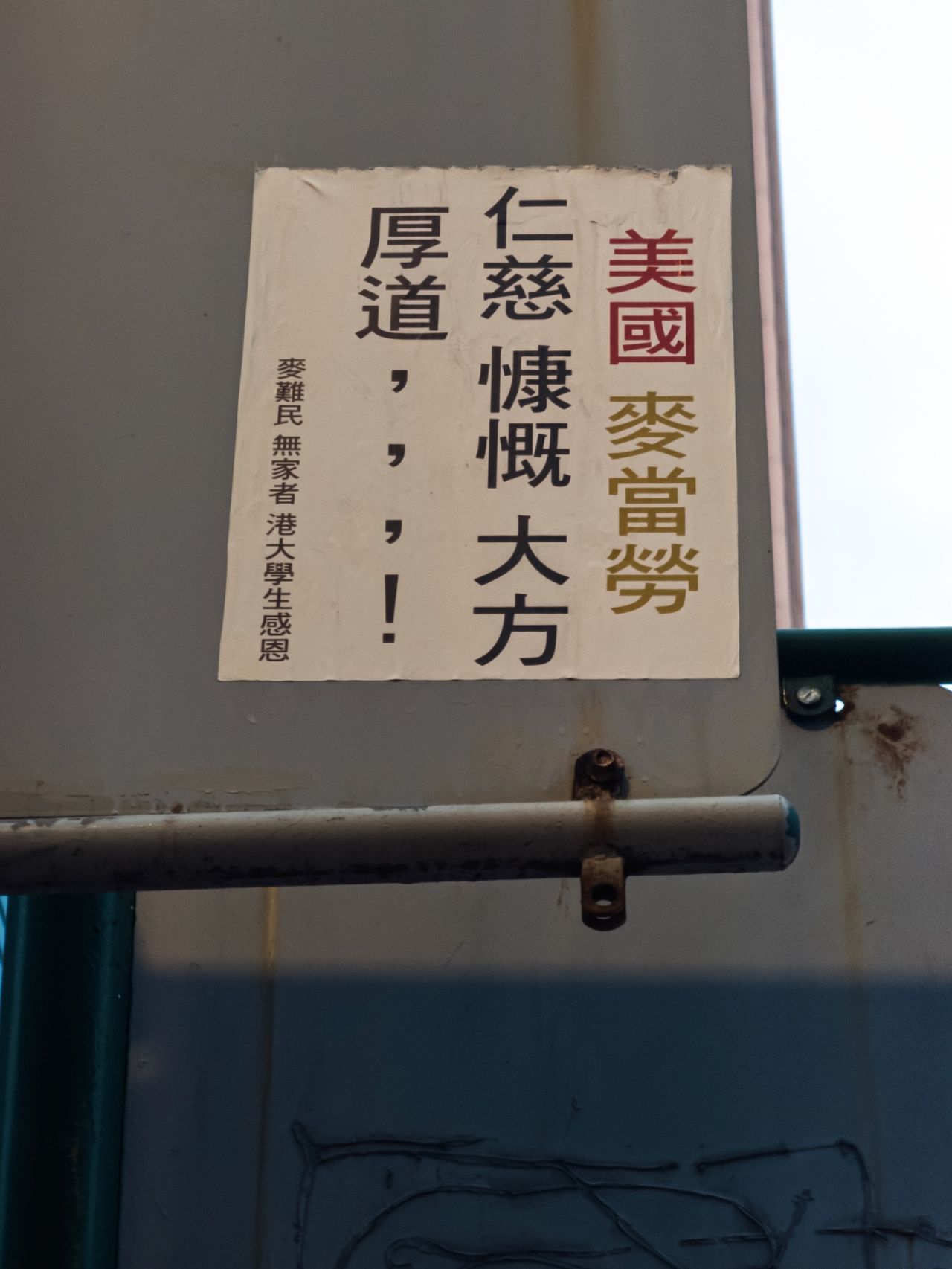

“No, Hong Kong’s Governance Is Not Becoming Like China’s. It’s Actually Worse.”:

Despite the authoritarian system under Beijing’s rule, mainland authorities do possess institutional mechanisms that absorb public pressure and enforce administrative responsibility in ways Hong Kong currently does not.

While mainland China is also guilty of suppressing criticism and dissent, it has the structural tools to pursue at least modest accountability, and the confidence to allow a tightly controlled safety valve for the fiercest anger.

Many of [Hong Kong’s] key accountability mechanisms were designed and institutionalized during the final decades of British rule, when the colonial government sought to develop Hong Kong into a prosperous global city grounded in professionalism, public accountability, and the rule of law.

These mechanisms, however, can function effectively only in a political environment that favors checks and balances.

Hong Kong has hollowed out the institutional mechanisms that once ensured accountability and effective governance, but it has not developed the structures that support stability in mainland China. The result is a governance vacuum, in which neither democratic nor authoritarian accountability functions effectively.

This structure traps Hong Kong between two governance models. It has weakened the institutions that once supported its administrative legitimacy, yet it cannot adopt the systems of performance-based accountability that make Chinese authoritarianism sustainable. In this context, political suppression becomes one of the few viable tools available to manage discontent.

As long as Beijing values the appearance of “One Country, Two Systems,” Hong Kong will not be able to replicate the mainland’s approach to crisis governance. But without rebuilding its own institutions of transparency and responsibility, the city risks further erosion of public trust and administrative capacity.

December 2025

Note (2025-12-28 21:39)

Note (2025-12-27 10:42)

The problem was setup.py. You couldn’t know a package’s dependencies without running its setup script. But you couldn’t run its setup script without installing its build dependencies. PEP 518 in 2016 called this out explicitly: “You can’t execute a setup.py file without knowing its dependencies, but currently there is no standard way to know what those dependencies are in an automated fashion without executing the setup.py file.”

This chicken-and-egg problem forced pip to download packages, execute untrusted code, fail, install missing build tools, and try again.

PEP 658 [putting package metadata directly in the Simple Repository API] went live on PyPI in May 2023. uv launched in February 2024. uv could be fast because the ecosystem finally had the infrastructure to support it. A tool like uv couldn’t have shipped in 2020. The standards weren’t there yet.

Wheel files are zip archives, and zip archives put their file listing at the end. uv tries PEP 658 metadata first, falls back to HTTP range requests for the zip central directory, then full wheel download, then building from source. Each step is slower and riskier. The design makes the fast path cover 99% of cases.

Some of uv’s speed comes from Rust. But not as much as you’d think.

pip copies packages into each virtual environment. uv keeps one copy globally and uses hardlinks (or copy-on-write on filesystems that support it).

uv parses TOML and wheel metadata natively, only spawning Python when it hits a setup.py-only package that has no other option.

Where Rust actually matters

uv uses rkyv to deserialize cached data without copying it. The data format is the in-memory format. This is a Rust-specific technique.

Rust’s ownership model makes concurrent access safe without locks. Python’s GIL makes this difficult. […]

uv is fast because of what it doesn’t do, not because of what language it’s written in. The standards work of PEP 518, 517, 621, and 658 made fast package management possible. Dropping eggs, pip.conf, and permissive parsing made it achievable. Rust makes it a bit faster still.

pip could implement parallel downloads, global caching, and metadata-only resolution tomorrow. It doesn’t, largely because backwards compatibility with fifteen years of edge cases takes precedence. But it means pip will always be slower than a tool that starts fresh with modern assumptions.

Note (2025-12-25 20:09)

“Why Millennials Love Prenups”:

For much of the twentieth century, judges almost always refused to enforce prenups, fearing that they encouraged divorce and thus violated the public good. They were also concerned that measures to limit spousal support could lead to the financially dependent spouse—usually the woman—becoming reliant on welfare. Nonetheless, in the twenties, as divorce rates increased, potentially pricey payouts became a topic of national debate. As the sociologist Brian Donovan observes in the 2020 book “American Gold Digger: Marriage, Money, and the Law from the Ziegfeld Follies to Anna Nicole Smith,” a veritable “alimony panic” set in. To avoid paying any, men transferred deeds, created shell companies, and, in New York, set up “alimony colonies” in out-of-state locales such as Hoboken, where they wouldn’t be served with papers. Even though courts were equally loath to award alimony—“Judges publicly criticized alimony seekers as ‘parasites,’ ” Donovan writes—the perception that men were being fleeced persisted.

There had been limited cases since the eighteenth century in which prenuptial contracts were recognized in the U.S., but these typically pertained to the handling of a spouse’s assets after death. The idea of a contract made in anticipation of divorce was considered morally repugnant. In an oft-cited case from 1940, a Michigan judge refused to uphold a prenup, emphasizing that marriage was “not merely a private contract between the parties.” You could not personalize it any more than you could traffic laws.

But by the early seventies there was no stemming the tide of marital dissolution: the divorce rate had doubled from just a decade earlier. In 1970, a landmark case, Posner v. Posner, was decided in Florida. Victor Posner, a prominent Miami businessman, was divorcing his younger wife, a former salesgirl. He asked the judge to honor the couple’s prenup, which granted Mrs. Posner just six hundred dollars a month in alimony. The judge, in his decision, acknowledged the cultural shift: “The concept of the ‘sanctity’ of a marriage as being practically indissoluble, . . . held by our ancestors only a few generations ago, has been greatly eroded in the last several decades.”

In the early eighties, following protests by women’s organizations, New York State had passed a new law that declared that all marital assets would no longer go by default to the titleholder—typically the husband—but would have to be divided according to “equitable distribution.” Judges were given a number of factors to consider in determining what was equitable, including the contributions of a “homemaker” to the other spouse’s “career or career potential.”

[T]hose living in poverty are typically splitting not assets but debts. In many cases, it’s “coerced debt”—the result of credit-card applications filled out by a spouse without a partner’s knowledge, for instance.

[Y]ounger generations might be seeking out prenups because there’s greater awareness now of the cost of litigation, both financial and emotional. […] [S]ome partners “file motion after motion just to wear down their victim, just to force them to try to walk away with less.”

We sign prenups in pen, but our lives are written in pencil; plans can easily get erased, vows smudged to the point of illegibility. “That’s why older people cry at weddings,” one divorce attorney told me. “Because we know that young couples don’t know what they’re getting into.”

Note (2025-12-24 22:25)

Note (2025-12-24 20:44)

“Why Does A.I. Write Like … That?”:

Every day, another major corporation or elected official or distant family member is choosing to speak to you in this particular voice. This is just what the world sounds like now. This is how everything has chosen to speak. Mixed metaphors and empty sincerity. Impersonal and overwrought. We are unearthing the echo of loneliness. We are unfolding the brushstrokes of regret. We are saying the words that mean meaning. We are weaving a coffee outlet into our daily rhythm.

Note (2025-12-24 06:17)

「豔屍文學」這個說法本身,我不認爲是一個僞命題。文學與藝術創作史中,大量創作者致力於創造出美麗的女性死亡的畫面。這裏的「美麗」,首先是這個死去的女性外貌必須美麗,她不可能是垂垂老矣,也不可能身材臃腫。在準備死亡的時候,她必定妝容完美,神情優雅;死亡發生的那一刻,這個女性甚至會帶上一絲仙氣。倘若是上吊死的,必定是一滴清淚一抹白綾,吊在繩上容色如初;倘若是高空墜亡,那衣服大概會仙氣飄飄,跌落之後姿勢優美,最好是紅色盛裝躺在雪地裏,映襯出最醒目的亮色。

德國比較文學學者 Elisabeth Bronfen 的 1992 年著作《Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic》,把西方創作中美麗女性的死亡作爲一個母題,分析對象包括維多利亞時代的繪畫、哥特小說、波德萊爾、普魯斯特、荷里活電影等,奧菲莉亞之死便是其中一個引述的重要例子。該作認爲,男性創作者面對死亡焦慮時,通過把死亡投射到女性身上,凝視女性的死亡,達致把死亡變成一種可控、可理解、可凝視的事物;女性死亡不只是死亡,而是被刻意美化的,是美麗、純潔、寧靜、具有象徵性,體現了文化對秩序、美、與控制的渴望。

魯迅在《幫閒法發引》一文中,這樣描述一個幫閒打諢的人如何描寫女性之死:「死的是女人呢,那就更好了,名之曰『豔屍』,或介紹她的日記。如果是暗殺,他就來講死者的生前的故事,戀愛呀,遺聞呀……而這位打諢的腳色,卻變成了文學者。」

若要下一個定義,我認為「豔屍文學」是指文藝創作中,作者對美麗女性死亡的奇觀式想像。它和東亞十分瞭解的死亡美學有一定共通之處,但又不完全一樣。這個年輕美麗的女性死亡場面,是對浪漫、青春乃至情色的寄情,甚至是在死亡那一刻賦予的某種神性;但唯獨不是死亡本身。唯獨不是面臨死亡時的痛苦、靈魂的熄滅和肉體的衰敗,唯獨不是一個鮮活人生本該發生的無限可能未來被攔腰斬斷,唯獨不是當威脅降臨時,一個人類本着求生欲和死神堂堂正正地搏鬥,最後遺憾但有尊嚴地輸掉這場比賽。

然而,當下網絡討論中用「弱女敘事」乃至「豔屍文學」批評《房思琪的初戀樂園》(以下簡稱《房》)一書,我認爲是不成立的。[…]《房》一書的刻劃,基本與豔屍圖景期望的目的背道而馳:整個故事慘烈邪惡,施暴者的畫面醜陋,當事人的痛苦真實,沒有人會讚美這樣的圖景,沒有人會嚮往這樣的死亡。

倘若「豔屍文學」概念本身還能溯源一二,所謂「弱女文學/敘事」我認爲幾乎是個僞概念。[…] 文學應當是平等的,或者說,虛構作品刻劃不同人的精神世界這件事,應當是平等的。沒有哪一種人是不值得被文學書寫的。文學的作用也不是「振奮人心」,如果是的話,我們只需要不停重寫各個版本的《基督山伯爵》就好了。

《房》一作以及其後世影響,最大的功績之一,就是使得一個犯罪現象被命名和看見。[…] 當有人可能不幸面臨類似處境,卻又無法釐清自己的困惑時;當有人想要控訴,卻很難說清自己的遭遇時——如今只要簡單地說出這個名字,我們就明白了。

Note (2025-12-23 06:13)

“The Word ‘Religion’ Resists Definition but Remains Necessary”:

[The Romans’] notion of religio once meant something like scruples or exactingness, and then came to refer, among other things, to a scrupulous observance of rules or prohibitions, extending to worship practices. It was about doing the right thing in the right way.

To arrive at the modern category of religion, scholars now tend to think, you needed a complementary ‘secular’ sphere: a sphere that wasn’t, well, religious. That’s why the word’s modern, comparative sense wasn’t firmly established until the 17th century – Hugo Grotius’s De veritate religionis Christianae (1627) is one touchstone – at a time when European Christendom was both splintering and confronting unfamiliar worlds through exploration and conquest. Even as religion could be conceived as a special domain that might be isolated from law and politics, the traffic with ancient and non-European cultures forced reflection on what counted as ‘true religion’. It’s just that, when Europeans looked at India, Africa, China or the ancient Mediterranean, they sifted for Christian-like (and often Protestant-like) elements: a sacred text to anchor authority, a prophetic founder to narrate origins, a set of theological doctrines to sort out orthodoxy and heresy, and perhaps duties that offered a path to salvation. If a tradition didn’t provide these, scholars might helpfully supply them.

[T]he biblical writers do not stand before the universe feeling compelled to develop a worldview; they stand within a covenantal drama, entwining law, story and communal identity.

True, where science posited impersonal forces, traditional thought posited personal ones. But the underlying move from observed regularities to theoretical constructs was similar; what Europeans wanted to call religion was a pragmatic explanatory framework, reasonable given the available evidence, and part of the same conceptual space as folk biology, folk psychology and everyday causal reasoning.

[S]uccessful reference doesn’t depend on getting the description right. What matters is the causal connection between our words and the things they’re meant to denote. […] Causal theories of reference explain why our words can target the same class of object even when our conception of it shifts, and when the boundaries of the class shift, too.

‘Religion’, like many social kinds, functions in both ways. Anthropologists can use the term to describe practices that their participants would never call religions, yet, once the label circulates, it acquires a reflexive power: believers come to organise their self-understanding around it. In this respect, religion is a product of classification that helps to shape the reality it describes.

The map may not be the territory, but we’d be lost without it.

Note (2025-12-22 22:10)

“On Citations, AI, and ‘Not Reading’”:

[T]he problematic way in which we use referencing as a signaling mechanism rather than purely as an epistemological phenomenon.

There is more to read in the contemporary world than can be read within a single lifetime. Therefore, all reading is subject to a type of economic decision making that rests on time as the unit of currency that is to be spent by an individual.

prayer (2025-12-20 11:54)

Note (2025-12-20 06:31)

karpathy reviews LLMs’ year of 2025:

Reinforcement Learning from Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) emerged as the de facto new major stage to add to this mix. By training LLMs against automatically verifiable rewards across a number of environments (e.g. think math/code puzzles), the LLMs spontaneously develop strategies that look like “reasoning” to humans - they learn to break down problem solving into intermediate calculations and they learn a number of problem solving strategies for going back and forth to figure things out (see DeepSeek R1 paper for examples). These strategies would have been very difficult to achieve in the previous paradigms because it’s not clear what the optimal reasoning traces and recoveries look like for the LLM - it has to find what works for it, via the optimization against rewards.

Unlike the SFT [supervised finetuning] and RLHF stage, which are both relatively thin/short stages (minor finetunes computationally), RLVR involves training against objective (non-gameable) reward functions which allows for a lot longer optimization. Running RLVR turned out to offer high capability/$, which gobbled up the compute that was originally intended for pretraining. Therefore, most of the capability progress of 2025 was defined by the LLM labs chewing through the overhang of this new stage and overall we saw ~similar sized LLMs but a lot longer RL runs. Also unique to this new stage, we got a whole new knob (and and associated scaling law) to control capability as a function of test time compute by generating longer reasoning traces and increasing “thinking time”. OpenAI o1 (late 2024) was the very first demonstration of an RLVR model, but the o3 release (early 2025) was the obvious point of inflection where you could intuitively feel the difference.

We’re not “evolving/growing animals”, we are “summoning ghosts”.

Supervision bits-wise, human neural nets are optimized for survival of a tribe in the jungle but LLM neural nets are optimized for imitating humanity’s text, collecting rewards in math puzzles, and getting that upvote from a human on the LM Arena. As verifiable domains allow for RLVR, LLMs “spike” in capability in the vicinity of these domains and overall display amusingly jagged performance characteristics

Related to all this is my general apathy and loss of trust in benchmarks in 2025. The core issue is that benchmarks are almost by construction verifiable environments and are therefore immediately susceptible to RLVR and weaker forms of it via synthetic data generation. In the typical benchmaxxing process, teams in LLM labs inevitably construct environments adjacent to little pockets of the embedding space occupied by benchmarks and grow jaggies to cover them. Training on the test set is a new art form.

LLM apps like Cursor bundle and orchestrate LLM calls for specific verticals:

- They do the “context engineering”

- They orchestrate multiple LLM calls under the hood strung into increasingly more complex DAGs, carefully balancing performance and cost tradeoffs.

- They provide an application-specific GUI for the human in the loop

- They offer an “autonomy slider”

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin. The ultimate reason for this is Moore’s law, or rather its generalization of continued exponentially falling cost per unit of computation. Most AI research has been conducted as if the computation available to the agent were constant (in which case leveraging human knowledge would be one of the only ways to improve performance) but, over a slightly longer time than a typical research project, massively more computation inevitably becomes available. Seeking an improvement that makes a difference in the shorter term, researchers seek to leverage their human knowledge of the domain, but the only thing that matters in the long run is the leveraging of computation. These two need not run counter to each other, but in practice they tend to. Time spent on one is time not spent on the other. There are psychological commitments to investment in one approach or the other. And the human-knowledge approach tends to complicate methods in ways that make them less suited to taking advantage of general methods leveraging computation. There were many examples of AI researchers’ belated learning of this bitter lesson, and it is instructive to review some of the most prominent.

We have to learn the bitter lesson that building in how we think we think does not work in the long run. The bitter lesson is based on the historical observations that 1) AI researchers have often tried to build knowledge into their agents, 2) this always helps in the short term, and is personally satisfying to the researcher, but 3) in the long run it plateaus and even inhibits further progress, and 4) breakthrough progress eventually arrives by an opposing approach based on scaling computation by search and learning. The eventual success is tinged with bitterness, and often incompletely digested, because it is success over a favored, human-centric approach.

One thing that should be learned from the bitter lesson is the great power of general purpose methods, of methods that continue to scale with increased computation even as the available computation becomes very great. The two methods that seem to scale arbitrarily in this way are search and learning.

The second general point to be learned from the bitter lesson is that the actual contents of minds are tremendously, irredeemably complex; we should stop trying to find simple ways to think about the contents of minds, such as simple ways to think about space, objects, multiple agents, or symmetries. All these are part of the arbitrary, intrinsically-complex, outside world. They are not what should be built in, as their complexity is endless; instead we should build in only the meta-methods that can find and capture this arbitrary complexity. Essential to these methods is that they can find good approximations, but the search for them should be by our methods, not by us. We want AI agents that can discover like we can, not which contain what we have discovered. Building in our discoveries only makes it harder to see how the discovering process can be done.

In this new programming paradigm then, the new most predictive feature to look at is verifiability. If a task/job is verifiable, then it is optimizable directly or via reinforcement learning, and a neural net can be trained to work extremely well. It’s about to what extent an AI can “practice” something. The environment has to be:

- resettable (you can start a new attempt),

- efficient (a lot attempts can be made) and

- rewardable (there is some automated process to reward any specific attempt that was made).

The more a task/job is verifiable, the more amenable it is to automation in the new programming paradigm. If it is not verifiable, it has to fall out from neural net magic of generalization fingers crossed, or via weaker means like imitation.

The computational substrate is different (transformers vs. brain tissue and nuclei), the learning algorithms are different (SGD vs. ???), the present-day implementation is very different (continuously learning embodied self vs. an LLM with a knowledge cutoff that boots up from fixed weights, processes tokens and then dies). But most importantly (because it dictates asymptotics), the optimization pressure / objective is different. LLMs are shaped a lot less by biological evolution and a lot more by commercial evolution. It’s a lot less survival of tribe in the jungle and a lot more solve the problem / get the upvote. LLMs are humanity’s “first contact” with non-animal intelligence. Except it’s muddled and confusing because they are still rooted within it by reflexively digesting human artifacts, which is why I attempted to give it a different name earlier (ghosts/spirits or whatever).

Note (2025-12-17 21:47)

“People Are Too Big to Fit Inside Our Heads”:

As long as we’re alive, we never completely coincide with ourselves. We’re free to go beyond what we’ve been and change. To treat someone as an object that you can understand and predict, therefore, is a bit like killing them, as Bakhtin writes. It’s to deny what’s most deeply human in us.

Note (2025-12-14 15:45)

“Why the World Should Worry About Stablecoins”:

“For the rest of the world, including Europe, wide adoption of US dollar stablecoins for payment purposes would be equivalent to the privatization of seigniorage by global actors.” This then would be yet another predatory move by the superpower.

Yet the [Bank for International Settlements] is also concerned that stablecoins will fail to meet “the three key tests of singleness, elasticity and integrity”. What does this mean? Singleness describes the need for all forms of a given money to be exchangeable with one another at par, at all times. This is the foundation of trust in money. Elasticity means the ability to deliver payments of all sizes without gridlock. Integrity means the ability to curb financial crime and other illicit activities. A central role in all this is played by central banks and other regulators.

Note (2025-12-13 10:21)

《當偶像突然變成系統敏感詞》:

即使追星和國家敘事表面上都有情緒、儀式、象徵物,即使有人會問:它們難道不是同一種情緒動員機制嗎?但它們的本質恰恰相反。

那是因為,國家的儀式、口號、循環播放的聲音,是排他的、單向的、要求一致性的:它把人組織成一個「必須相同」的整體,你必須相信、必須感動、必須站立、必須沉默。

而我們在演唱會里感受到的,卻是完全不同的東西:它是非強制的、開放的、自願的;它允許每個人帶着自己的傷口、自己的故事、自己的目光進入這個共同體。

比起在古拉格相關的文本中尋找可以譴責古拉格的點,更重要的是,詢問這些文本如何使得古拉格成為可能,(這些文本)可能至今仍在自圓其說,讓難以忍受的真理直到今天仍被廣泛接受。關於古拉格的問題,提出的角度不應是做錯了什麼(把問題降至理論的維度),而應該把古拉格作為一個存在着的現實來討論。

Note (2025-12-11 06:24)

“I am a Stranger” [我是陌生人] by Xiang Biao [项飙], as an introduction to the book Hello Stranger [你好,陌生人], CITIC Press (2025).

Translated (with abbreviation) by David Ownby; supplemental translations and emphases mine.

[I]t was only in modern times that “stranger” became a relatively stable concept, after a long period in which the idea occupied a prolonged intermediate status somewhere in between.

只有到了现代,“陌生人”成为一个相对稳定的概念,他们长期处于既不是敌人也不是客人的中间状态。

In fact, the realization that there are many people in the world that we don’t know—and that these people might at the same time be connected to us—is itself a modern phenomenon.

意识到世界上有很多我不认识的人,而且这些人可能和我有关,这本身是一个现代现象。

If one of the defining features of the modern era is that people came to understand that distant strangers might be related to them, today the reverse seems to be occurring: we are starting to feel that people we know are unfamiliar to us. Ultimately, this kind of alienation also means that we become strangers to ourselves, unable to recognize who we truly are and what we really want.

如果说,在经典的现代状态下人们意识到陌生人是跟自己有关的,那么在今天,人们感到认识的人和自己无关。到最后,“陌生化”也意味着自己成了自己的陌生人。自己不能够认得自己究竟是谁,不知道自己要什么。

Strangers remain strangers, never becoming friends, enemies, or guests, never communicating ambiguity, surprises, shadows, or highlights.

一个个陌生人就是一个个清晰的陌生人,他们不会转变成朋友、敌人、客人,不会带来暧昧、惊喜、阴影、高光。

Life has become transparent yet impermeable, part of the abstraction of the public sphere. Transparency clearly implies the notion of public—a space where everyone is fully exposed and has no place to hide—but this public is not constructed through our mutual interactions. Instead, it is shaped by third-party systems that permeate every aspect of our lives. These third parties define all individuals, dictate their behavior, and hold them directly accountable. A public sphere formed through horizontal interactions between individuals is not transparent but rather porous; the public sphere established by a unified third party is abstract and transparent.

生活变得透明而不透气,是和公共的抽象化联系在一起的。透明显然意味着公共——大家在这里一览无余甚至无处遁形,但这个公共不是由无数个体通过互动搭建出来的,而是靠一个全面贯穿我们生活的第三方系统捏合而成的。这个第三方定义所有的个体,规定所有个体的行为,所有的个体都直接对第三方负责。通过个体间横向互动而形成的公共是不透明的,而是透气的;通过一个统一的第三方建立的公共是抽象的也是透明的。

When everything is transparent, this kind of abstracted public can lose its content. For example, moral considerations may become meaningless. People have moral questions largely because of limited information. When things are not transparent, people need to make judgments and choices, which is why they need morality, which allows people to continue to interact meaningfully even in the absence of transparency.

当一切都是透明的,抽象的公共性往往也失去了内容。比如道德考虑可能变得虚无。人类之所以有道德问题,很大程度上是因为人们信息有限。在事情不透明的情况下人们需要做出判断和选择,这时候人们就需要道德,道德使人和人可以在不透明中继续有意义地交往。

In a transparent world, a person’s fate is already determined by the powers that be; an uncertain future is an individual’s misfortune and it has no meaning. At the same time, if a person truly conforms to the rules of the transparent world, these unpredictable events can be overcome and transformed into predictable ones. The meaning of life seems to lie in overcoming one’s own opaque experiences according to the slogans that hang on the walls and in the air, thereby becoming a person everyone can recognize. Finally, transparency is the way society is organized, an image through which people understand personal and social relationships, and thus also becomes their objective state of existence.

在透明的世界,人的命运已经被系统的力量决定了,未卜的前途是个人的不幸,它们没有意义;同时,如果一个人真正符合了透明世界的规则,这些未卜事件都可以被克服,变成可卜。人生的意义似乎就在于按照那些写在墙上、挂在空中的标语来克服自己那些不透明的经历,变成人人认可的人。归根到底,透明是社会组织的方式,是人们理解个人和社会关系的一个意象,从而也成为人们客观的存在状态。

The sense of being a stranger felt by the small-town test-takers reflects the nature of Chinese social life, which again is transparent but impermeable. We see the transparency in the fact that their life trajectories and achievements accord with the standards and expectations set by the system, leading to the expected stamp of approval. The impermeability lies in their inability to freely express their personal struggles, hesitations, and anxieties. While they have earned approval, what they lack is recognition in the sense of being understood and seen. Approval is the system’s evaluation of an individual’s achievements based on predetermined standards, determining whether to reward or punish. Recognition, by contrast, involves agency: it is one subject’s comprehension of another subject—seeing that person’s emotions, thoughts, struggles, and history, with no relation to testing, judgment, or rewards and punishments.

小镇做题家的陌生感,反映了社会生活“透明不透气”的特征。他们生活的透明性体现在,他们的成长轨迹和成绩符合体系规定的标准和预期,被毫无悬念地认可。他们体会到的不透气,体现在他们无法从容地表现个人的挣扎、犹豫和苦恼。他们获得了“认可”,欠缺的是“认得”。认可是系统根据既定的标准,评价一个人的成果,决定给予奖励还是惩罚。认得,则是一个主体对另外一个主体的理解,是一个人对另一个人的情绪、考虑、挣扎和历史的看见,它不涉及考验、判断和奖惩。

The issue we are currently facing is not merely that approval has replaced recognition; more critically, approval has become the very basis of recognition. The idea that “love is conditional”—you will only be loved if you prove you are worthy—is a significant reason why many young people feel from an early age that life is a burden. Most of them do not lack love, but the conditional nature of love instilled by family, school, and society has turned nurturing into a burden. The condition for obtaining love and understanding is to first obtain approval. The reason many people sacrifice so much time and effort in pursuit of approval is precisely because this is the first step to earning recognition—when I prove that I am normal and successful, I earn attention, understanding, and love.

我们现在面临的问题,不仅仅是认可取代了认得,更严重的是,认可成了认得的基础。“爱是有条件的”——你要证明你值得爱,爱才存在——是不少年轻人从小感到生活沉重的重要原因。他们中的大部分人并不缺乏爱,但是家庭、学校和社会灌输的爱的“条件感”让滋养变成了负担。而获得爱和认得的条件,就是要先获得认可。很多人之所以要牺牲这么多时间和精力来追求认可,正是因为这是他们获得认得的基础——通过证明我是正常的、成功的,以获得关注、理解和爱。

Husserl argued that the process by which we know the world is not one of discovering an objectively existing external world, but rather one of perceiving the world through experience. Therefore, the nature of one’s experience—the “lifeworld”—determines the kind of world one perceives. Following Husserl’s concept, Schütz emphasized the lifeworld as the “paramount reality of everyday life.” It is the only real world for the individual because it is the world people realize directly through their own experiences; it is not defined by concepts or theories, but formed directly by the senses and experience. Existence beyond the lifeworld, such as the “educational system,” “labor market,” or “technological sector,” is virtual. Habermas extended this further, arguing that the mutual understanding formed through direct human interaction in the lifeworld is the foundation of effective democracy; we must be wary of the “system” (especially state power and market forces) encroaching upon the lifeworld. Although we may not agree that the lifeworld is the foundation of the entire social meaning system, we must admit that the lifeworld directly affects our cognition of society and ourselves. A narrow lifeworld weakens a person’s experiential foundation; they may have a strong self-consciousness, but they lack the “stock of knowledge at hand” (Schütz) to form a rich understanding of others or careful judgments of social situations, thus failing to establish effective distance.

胡塞尔认为,我们认识世界的过程,并不是一个客观存在的外在的世界等待我们去发现,而是我们通过经验来认知世界。所以,什么样的经验(生活世界)决定了我们会感知到什么样的世界。舒尔茨沿用胡塞尔的生活世界概念,强调它是“前概念存在”,是对个人来说唯一真实的世界,因为它是人们直接根据自己的经验而意识到的世界,它不是靠概念、理论去定义的,而是感官和经验直接形成的。超越生活世界的存在,比如“教育系统”“劳动力市场”“科技界”都是虚拟性的。哈贝马斯进一步延伸,认为生活世界里通过人和人直接交流形成的互相理解,是有效民主的基础;我们必须警惕“系统”(特别是国家权力和市场力量)对生活世界的侵占。尽管我们不一定同意生活世界是整个社会意义系统的基础这个说法,但是我们不得不承认,生活世界直接影响我们对社会和对自己的认知。狭窄的生活世界使人的经验基础变得非常薄弱,他可以有强烈的自我意识,但是没有形成可以调用的“知识储备”(舒尔茨)对其他人形成丰富的理解,对面临的社会情况形成仔细的判断,从而不能形成有效间隔。

The understanding that “we are all the same” can also lead to alienation. ... We may be lonely because we can’t find anyone like us, but we may also be lonely because everyone around us is just like us. The meaning and destination of life have already been defined; everyone is a copy of one another. There is nothing to say, and no need to speak. I call this “negative empathy”.

“大家都一样”的想象也会导致陌生化。一个人感到孤独,可能是因为你找不到和你相似的人,但也可能是因为当你放眼望去,到处都是和你相似的人。生命的意义和归宿都已经被定义好了,大家都是对彼此的复制。无可言说,不需要言说。所以我称之为“反向共情”。

“Negative empathy” is a construct created by humans. The “utilitarian assumption” is one aspect of this process of construction. The utilitarian assumption does not mean imagining one another as competitors but refers instead to the idea that people should understand the world and handle interpersonal relationships based on this assumption. Since everyone makes their own calculations when doing things, it is best not to ask too many questions, nor is there any need to do so. The utilitarian assumption also serves as a reminder to focus attention on matters that can bring tangible benefits, and not to concern oneself with matters that have no direct consequences. This differs from judging others according to one’s standards or putting yourself in someone else’s shoes. When you do either of these, the “self” is clearly defined, and the assumption is that others are the same as oneself. // However, negative empathy and utilitarianism do not have a clear sense of self as their starting point. They emphasize that all people “ought” to be the same, and one should align one’s thoughts and actions with this “ought.” It is not about putting yourself in another’s shoes, but rather “putting others into your shoes.” The utilitarian assumption is, in a certain sense, also a self-protection mechanism. It does its best to eliminate the emotional, complex, subtle aspects of life that cannot be optimized, making the world simple and transparent, making thoughts swift and smooth, a single logic capable of explaining everything.

“反向共情”是一个人为建构的结果。“功利化假设”是其建构过程中的一个侧面。功利化假设并不意味着把彼此想象成竞争对手。它指人们应该按此预设去理解世界和处理人际关系。既然大家做事情都有各自的计算,所以最好不要多问,也不必多问。功利化假设也是在提醒自己:把注意力集中在那些最能够带来真金白银的事情上,对没有直接关系的事情没必要去管。这和以己度人、由己及人不一样。以己度人和由己及人中的“己”是明确的,从确定的自我意识出发,假设别人和自己是一样的。而反向共情和功利化假设并没有一个清晰的自我意识作为出发点。它强调的是所有的人“应该”一样,要按照这个“应该”来设定自己怎么想和怎么做,不是以己推人,而是以人推己。功利化假设在一定意义上也是一个自我保护机制。它把生活里那些情感上的复杂、细微、不能功利化的内容尽量剔除,世界从而变得简单而透明,思考因此快速而丝滑,单一的逻辑可以解释所有的事情。

Another mechanism for constructing negative empathy is “dehistoricization,” which involves discarding to the extent possible those parts of one’s life that are undignified, do not meet mainstream expectations, and are unrelated to current interests.

建构反向共情的另一个机制是“去历史化”,即把自己生命中不体面的、不符合主流期待的、和眼前的利益追求没有关系的那些部分尽量切除。

When we say “hello, stranger,” it does not mean that we consider ourselves natives of a particular place or even people who have found a place to settle down. However, to reflect carefully on the subjectivity of the statement “I am a stranger” and think about the state of stranger-making, we cannot think of it from the perspective of a stranger or an outsider. What we need is a new “grounded” way of thinking.

“你好,陌生人”,我们说这句话,并不意味着我们认为自己是本地人,是已经找到安身立命之所的人。但是,要细致地分析“我是陌生人”这样的主体性位置,反思陌生化的状态,又不能够以一种陌生人、局外人的方式来思考。我们需要的可能是一种“安生式”的思考。

So if Heidegger’s notion of dwelling focuses on the relationship between humans and nature, and humans and themselves, Pan’s adaptation emphasizes social relationships and social ethics. My idea of “groundedness” aims to combine these two concepts.

借用潘光旦的话,我们可以说海德格尔的栖息是“人本主义”的(关注人和自然、人和自己的关系),位育是“人文主义”的(强调社会关系和社会伦理)。“安生”希望把这二者结合起来。

A grounded style of thinking is based on the awareness that changing the status quo cannot be achieved through a single action or decision but rather requires a new understanding of life. From this new understanding, new behaviors, new relationships, and new meanings of life emerge. This new understanding must be grounded in concrete reality and confront various complexities: Why do I always feel like a stranger? Why do I unconsciously compare myself to others? Why is it so difficult to accept certain criticisms? Rather than making a blanket judgment about life—Why isn’t life the way I want it to be? why is everything unjust and unequal?—grounded thinking involves “consciousness-raising” of one’s own experiences.

安生式的思考是基于这样的意识:改变现状,不能靠某个行动、某个抉择,而必须对生活形成新的理解,从新的理解出发长出新的行为、新的关系、新的生活意味。这种新的理解必须是基于具体现实的,直面各种纠结(为什么我总觉得自己是个陌生人?为什么我会下意识地和别人比较?为什么我难以接受这样或那样的评论?),而不是要对生活做总体的好坏判断(为什么生活不是我想要的样子?为什么一切都是不正义、不平等的?)。

To develop a grounded way of thinking, the first step might be to treat thinking as a practical process, that is, to recognize that thinking is inseparable from observation, memory, bodily perception, expression, and dialogue. […] Whether we are getting to know acquaintances, recognizing strangers, or understanding ourselves, we first become aware of the specific scene, and then understand the people within that scene through the scene itself. […] This emphasis on the scene first implies viewing a person as a condensation of their historical experiences. […] The scene also implies that we must pay full attention to people’s positions within social relationships. […] Recognizing strangers and engaging in grounded thinking is a constantly repetitive process; it needs to occur repeatedly within the “flow of life” and requires a scene for observation and reflection.

要发展安生的思考方式,第一步可能是把思考处理为一个实践过程,即意识到,思考是和观察、记忆、身体感知、表达、对话不可分割的。[…] 不管是在了解熟人、认识陌生人,还是认识自己的时候,我们都是先意识到具体的场景,再通过场景来理解场景中的人。[…] 对场景的重视,首先意味着把人看作他的历史经历的浓缩。[…] 场景也意味我们要充分注意人们在社会关系中的位置。[…] 认得陌生人、安生式的思考是一个不断反复的过程,它需要在“生活流”里重复发生,需要一个观察和思考的场景。

Note (2025-12-10 22:00)

“Reading Lolita in the Barracks”:

A bugle call jolts you awake, bringing the dislocation of waking up in a strange place. You’re expected to spring up and fold your sleeping pad. If there's a straggler, the entire platoon must hold a punishing pose resembling a downward dog, often for a full hour. To this day, you still don’t understand why people pay to do yoga.

While I was sad to leave the friendships I'd forged in that blitz, I was suspicious of this orchestrated intimacy — one that must be reliably reproducible in Nonsan, under the engineered conditions of shared misery and resentment toward our drill sergeants. Was this kind of ready-made camaraderie the particular fiction that underwrites the enterprise of war? In the end, I’d never see most of them again. Perhaps friendship is what’s born of shared sensibilities, and we reserve the word camaraderie for what’s born of shared hatred.

Yongsan Garrison is the strangest place I’ve ever been. Having lassoed a prime stretch of land in the now-fashionable Itaewon district, it occupied more than half the area of Central Park, right in the heart of Seoul. But on Google Maps — coordinates (37.54, 126.98) — you’ll find a conspicuous blank space where it should be.

To put legions of young men on the cusp of manhood together is to create a petri dish of male ego. The military can serve as, to steal a phrase from D. W. Winnicott, a permanent alternative to puberty.

Even within the same rank, your month of enlistment mattered. An August recruit (me) was forever junior to a July recruit of the same year; it was common to call someone by their enlistment month. I was, for a time, simply “August.”

Officially, after lights-out at 10 p.m., there were two hours of voluntary study. It's a standard policy on every base to have a 연등실 (延燈室), which has the uncharacteristically poetic translation of "the Room Where the Lights Stay On."

Two or three hours every few nights were hardly enough. I began finding ways to outwit the system during my day job. Books were too conspicuous, so I printed out magazine articles, essays, and book chapters in what was surely unauthorized use of military computers. I shuffled these printouts in with my translation tasks, all practicing, in Gulag slang, tufta — “the art of pretending to work.” As long as the papers were in English, the officers didn't notice. Once I'd finished, off to the shredder they went.

Books brought from outside required navigating the military’s censorship apparatus. There was an official list of banned books — selected with the predictable logic of the conservative administration — that included Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang’s anti-neoliberal critique, Bad Samaritans. (Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century made the list in 2016.) Every book brought onto the base required an approval stamp from a censoring officer.

As a private joke with the bureaucracy, I submitted Lolita for approval. To the censoring officer, it was just another book written in a foreign language. He stamped it without comment. My copy still bears the imprint: “Military Security Clearance Passed.”

In the outside world there’s a divide between public and private morality: the stickler for recycling who’s a terror to her friends; the man kind to his neighbors but votes for tyrants. In the barracks this boundary vanished. There was no public life, only private morality in its most naked form, namely, your character.

The empathy literature fosters can be turned to any end — to help or to harm, to liberate or to oppress — as Nehamas notes, “well-read villains, sensitive outlaws, tasteful criminals, and elegant torturers are everywhere about us.”

The dubious gift of military service is that most South Korean men are sufficiently tested. For those of us honest with ourselves, we know how petty we can be.

Yet, as Rorty warns, in that very quest for autonomy lies a potential for cruelty: “our private obsessions with the achievement of a certain sort of perfection may make us oblivious to the pain and humiliation we are causing.” Which is to say, I may not have been cruel, but that doesn't mean I was virtuous.